Between March and November 2025, federal agents across Florida’s panhandle discovered dozens of men and women removed from the country multiple times, living undetected in American communities. One man, Denis Arnaldo Mendoz-Martinez, had been deported four separate times—2012, 2016, 2018, 2019—yet kept returning.

By January 2026, that pattern had resulted in 34 convictions, which federal prosecutors described as a stunning enforcement failure: deportation orders that simply didn’t hold.

A Coordinated Federal Push Across the Sunshine State

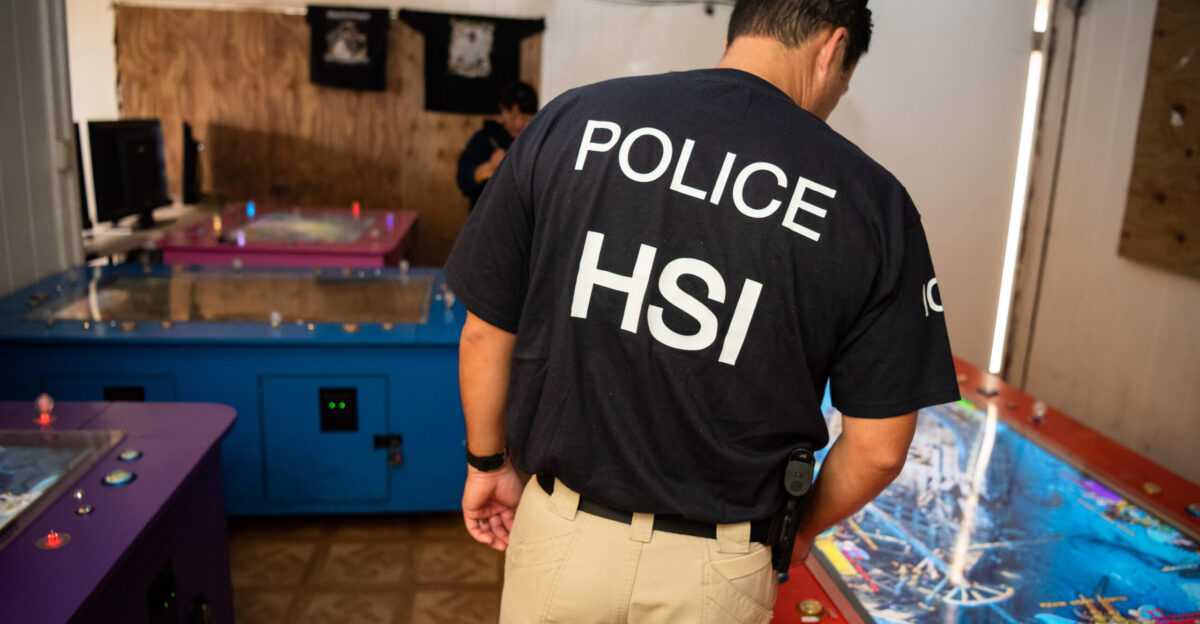

“Operation Take Back America,” a nationwide DOJ initiative, brought together ICE Homeland Security Investigations and ICE Enforcement & Removal Operations across six Florida counties—Leon, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Escambia, Alachua, and Bay.

U.S. Attorney John P. Heekin led the Northern District’s charge, coordinating seamlessly across agencies. What emerged was a vivid picture of repeat offenders navigating detection, crossing borders illegally multiple times, and rebuilding lives in the same country that had deported them.

The Conviction Breakdown

Thirty-one defendants were prosecuted for illegal reentry after prior deportation—a federal felony carrying prison time and another removal order. Four defendants faced additional charges: using false documents to facilitate their illegal return or stay.

The cases represented months of investigation, with convictions secured starting in September 2025 and announced on January 2, 2026.

Who Were the 34?

The defendants were primarily Mexican nationals, with smaller numbers from Honduras, Guatemala, and Panama—reflecting broader Southwest border crossing patterns where Mexican and Central American nationals dominate apprehension statistics.

Yet these weren’t first-time border crossers. All 34 had prior deportation orders on file, making their return a direct federal crime under U.S. immigration law.

A Pattern Within the Pattern

Denis Arnaldo Mendoz-Martinez’s case represents the most extreme. First removed April 2012, then February 2016, December 2018, and October 2019. Despite four formal deportations spanning seven years, he reentered and was apprehended again.

His case poses the central question haunting enforcement officials: what happens when deportation orders fail? How do repeat offenders cross back, evade detection, and establish communities here?

Leon County’s October Surprise

On October 8 and 9, 2025, federal agents made four arrests in Leon County—a concentrated two-day sweep signaling coordinated intelligence about reentry routes. In Okaloosa County, they found Jose Victor Aguilar Zelaya, deported in 2010 but discovered in March 2025, fifteen years after his initial removal.

The clustering suggested not random luck but intelligence-led enforcement across multiple jurisdictions.

The Cost in Taxpayer Dollars: Half a Million for One Operation

Each deportation costs federal agencies $10,000 to $15,000 in enforcement, detention, processing, and removal. The 34 convictions alone represent direct costs of $340,000–$510,000. However, when considering the estimated 70-plus prior deportations collectively across all 34 defendants, the cumulative federal spending exceeds $700,000 to $1 million.

Those figures exclude prosecution costs, investigative hours, and state law enforcement resources.

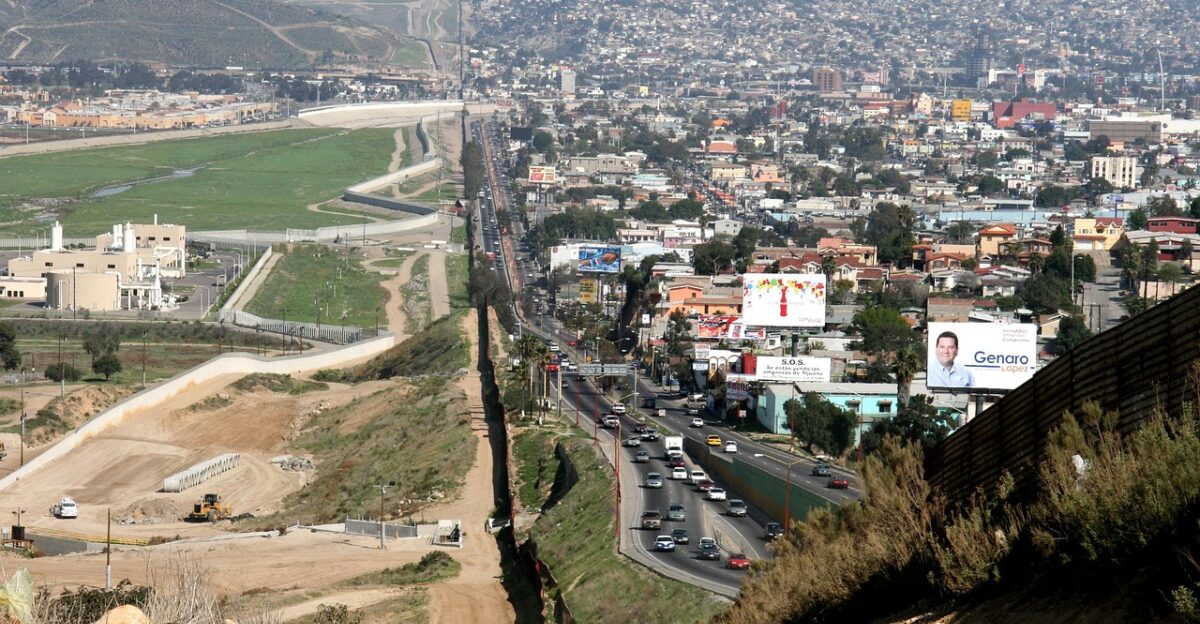

Geography and Enforcement Gaps

The panhandle’s concentration—comprising Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, and Leon—revealed how reentry works geographically. These areas offer anonymity and distance from major cities, yet remain close to agricultural, construction, and hospitality jobs.

Smaller counties typically have fewer immigration enforcement resources, creating natural hubs for individuals seeking to avoid detection.

The Nine-Month Window: Intensified Federal Attention

The period from March to November 2025 wasn’t random. It represented an intensified federal focus on illegal reentry, with investigators deliberately targeting individuals suspected of reentering after prior removal.

Convictions began flowing in September. By January 2, 2026, when the DOJ announced the batch, the message was clear: repeat offenders were in the DOJ’s sights.

What “Removal” Actually Means

A critical misunderstanding clouds deportation debate: removal and permanent expulsion aren’t synonymous. A deportation order bars legal reentry for a specified period—typically five to ten years for first-time removals, and longer for repeat offenses. But it doesn’t seal borders.

People cross illegally. They hide. They work under the table. They assume new identities. Denis Arnaldo Mendoz-Martinez’s four deportations underscore this vulnerability.

The Investigation Pipeline: From ICE to Federal Court

ICE Homeland Security Investigations conducts detective work—tracking suspected reentrants, verifying deportation records, and building cases with evidence of unlawful reentry. ICE Enforcement & Removal Operations coordinates arrests and detention.

Once charged federally, the U.S. Attorney’s Office prosecutes the case. The operation required seamless coordination across all three functions.

John P. Heekin Leads the Charge

U.S. Attorney John P. Heekin, head of the Northern District of Florida, made clear his office’s commitment to aggressive prosecution.

His statement emphasized the momentum of enforcement: “We are a nation of laws, and we will deploy the full resources of the federal government to keep our borders secure and our communities safe.” His office became the nerve center for Operation Take Back America’s Florida component.

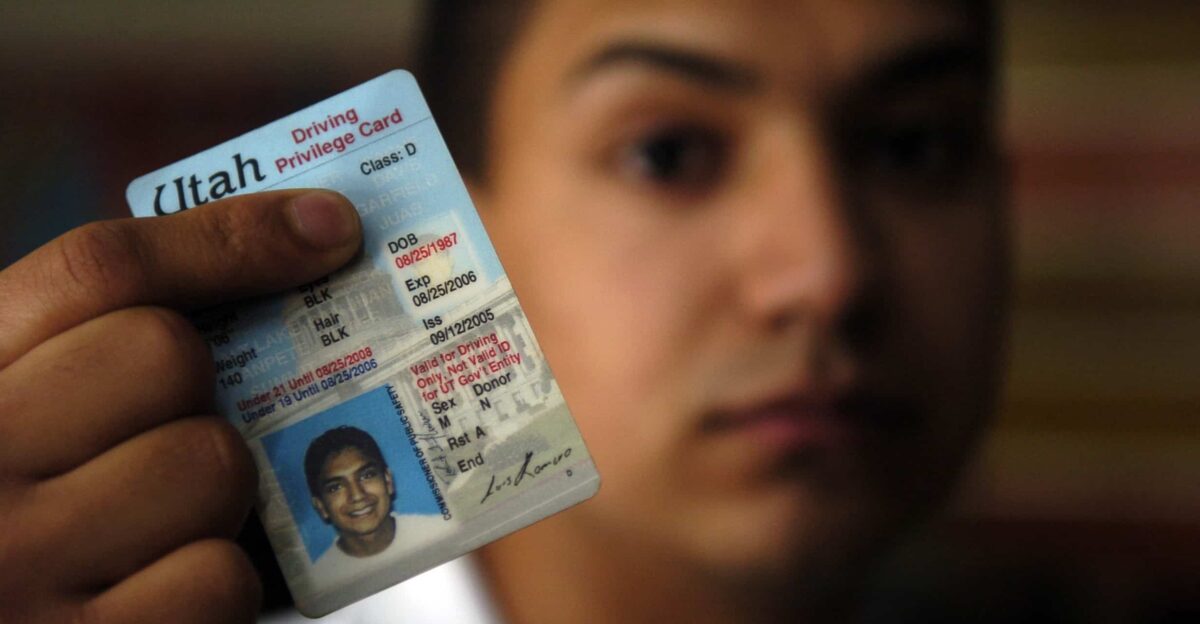

False Documents and Hidden Lives

Beyond reentry charges, four defendants faced document fraud prosecutions—using or possessing false identification, work permits, or travel papers to hide immigration history or establish employment legitimacy.

These charges compound legal jeopardy. A defendant convicted on both counts faces significantly stiffer federal penalties and extended incarceration.

A Nationwide Enforcement Momentum

Operation Take Back America extended beyond Florida. The DOJ characterized it as nationwide, implying similar enforcement actions were underway across multiple field offices.

If Florida’s Northern District convicted 34 individuals in nine months, extrapolation to Texas, Arizona, California, and other high-enforcement districts suggests hundreds of annual convictions nationally—a significant acceleration in historical enforcement patterns.

Identity Fraud as Enabler

Individuals who successfully reenter often obtain fraudulent identification to establish a legitimate employment history, secure housing, or conceal their immigration status during routine background checks.

Prosecutors in these cases highlighted “a growing trend of repeat illegal entries combined with identity fraud.”

Three Months from Arrest to Conviction

Four defendants arrested on October 8-9, 2025, in Leon County had their convictions announced on January 2, 2026—a roughly three-month window from arrest to federal conviction. This compressed timeline suggests either expedited federal processing or that other defendants were arrested and processed on different dates.

The announcement bundled cases from multiple arrest dates into a single DOJ press release—a standard practice that also reflects coordination and messaging strategy.

Two Decades of Deportation History

The earliest deportation in this batch occurred in 2006, while the latest field encounter took place in November 2025. This twenty-year span illustrates a persistent enforcement challenge: deportation orders issued two decades ago haven’t proven permanent barriers to reentry.

The federal government is spending billions on deportations, yet some individuals removed at significant cost return multiple times. Border security gaps? Inadequate tracking? Economic pull of U.S. employment? The record alone doesn’t answer.

Federal Authority, Community Safety, and Enforcement Narrative

The convictions arrive as the Trump administration prioritizes immigration enforcement. The DOJ announcement explicitly ties these convictions to federal authority, national security, and community safety language.

Heekin’s statement about “deploying the full resources of the federal government” and ICE Director Walker’s conditional messaging about voluntary versus forced removal reinforce a narrative that federal immigration authority is expansive and decisive.

Prison, Deportation, and the Unanswered Question

The 34 convictions await federal sentencing, where judges will impose sentences within statutory guidelines. Prison time will precede or run concurrent with deportation. All 34 defendants had prior removals on file, so judges will almost certainly issue consecutive removal orders.

The central unanswered question: what prevents those deported—even after prison—from attempting reentry again?

What This Moment Signals

Operation Take Back America represents more than 34 convictions; it signals federal enforcement escalation likely to accelerate nationwide. Similar operations in high-enforcement districts could produce hundreds of convictions annually.

The January 2, 2026 announcement came days into the new year—positioning these convictions as an early enforcement statement. Whether this momentum will reduce repeat reentry rates or simply increase prosecutions of an existing behavior pattern remains to be seen, as it will be determined by future data.

U.S. Department of Justice, Northern District of Florida, “Operation Take Back America” announcement, January 2, 2026

U.S. Attorney John P. Heekin, official statement, January 2, 2026

ICE Acting Field Office Director Kelei Walker, statement on voluntary return incentives, January 2, 2026

ICE Homeland Security Investigations case files, March–November 2025

Federal Bureau of Investigation criminal investigation records, 2025–2026

U.S. Federal Courts Northern District of Florida conviction records, September 2025–January 2026