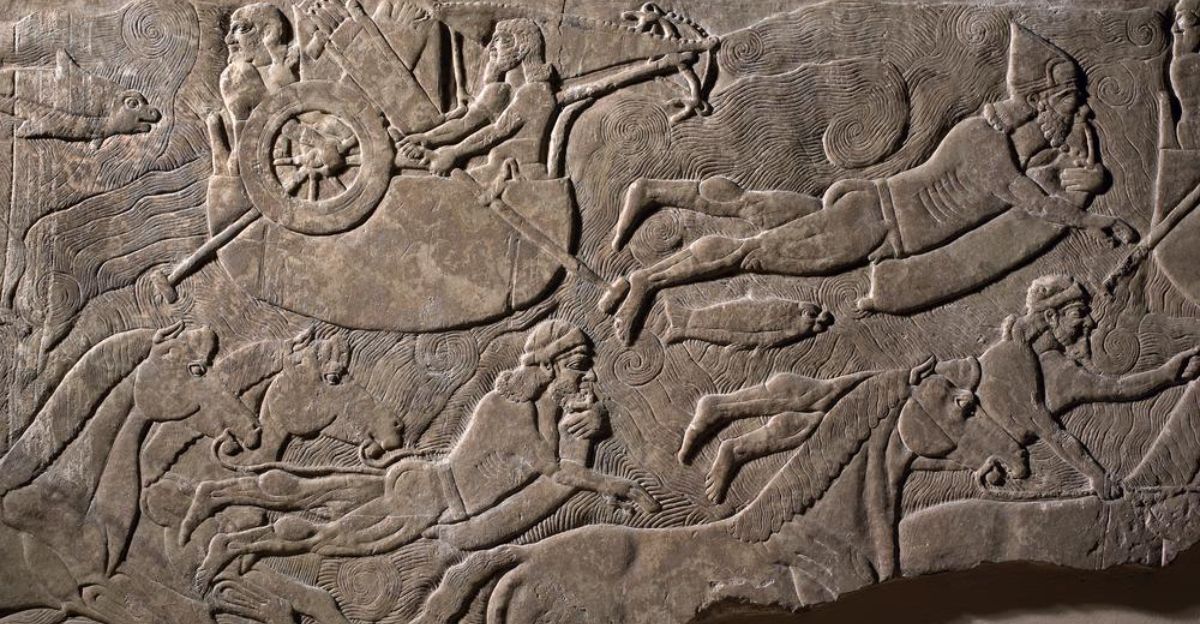

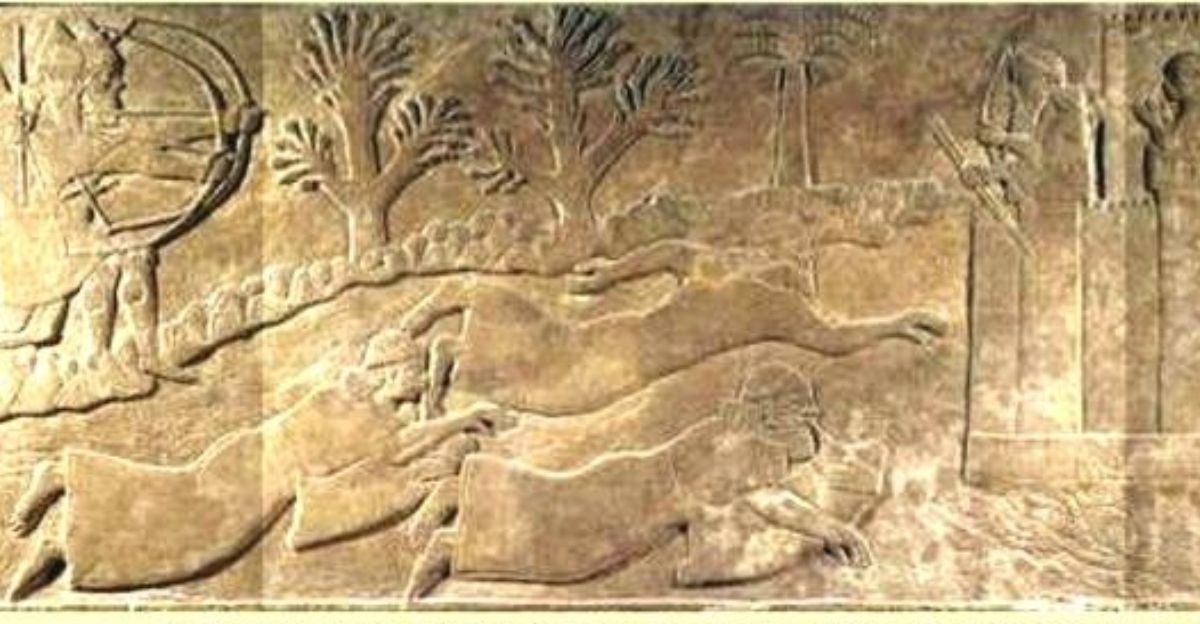

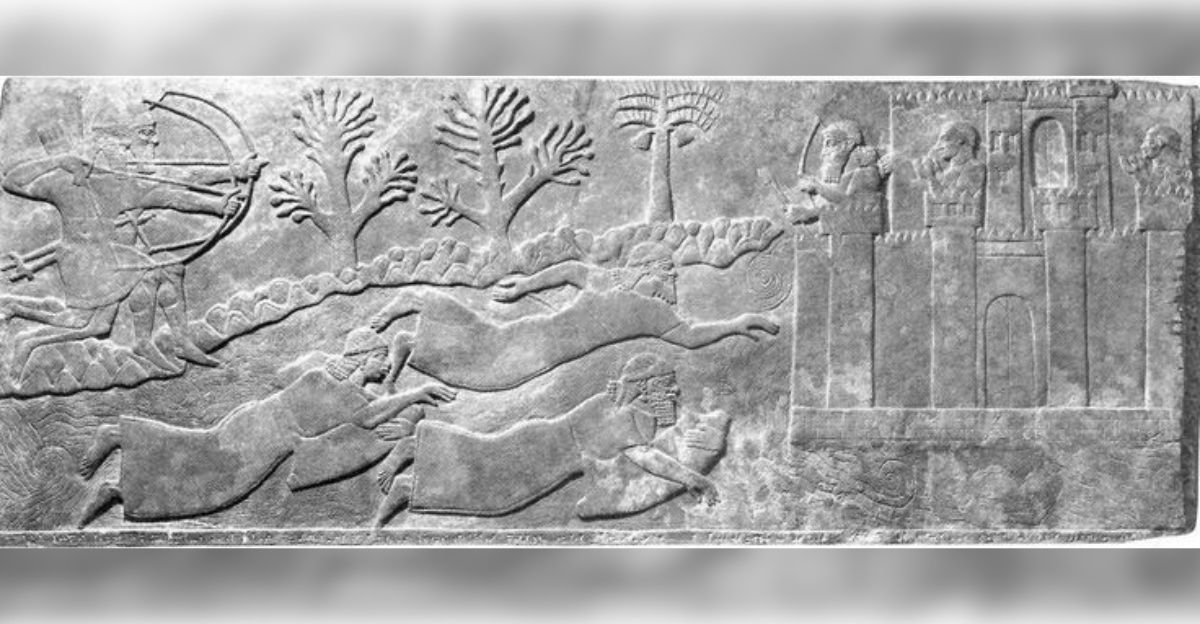

When people think of the Navy SEALs, they often imagine cutting-edge technology and modern tactics. However, a stone carving from the British Museum, dating back 2,885 years, shows something extraordinary.

Assyrian soldiers used inflated goatskins to cross rivers during military campaigns. The museum’s catalog describes these ancient warriors as specialized water-based military units.

Terror Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was once a feared nation that dominated the ancient world through its brutal warfare tactics.

By 700 BC, they controlled land from Egypt to Iran. Their military success came from iron weapons, psychological warfare, and surprise water attacks that terrorized enemies.

Water Problems

Ancient armies encountered the unique problem of river crossings during military campaigns. Traditional methods, such as building bridges or finding shallow areas, were slow and noisy.

Enemy forces could easily spot and attack soldiers while they were vulnerable, crossing water.

Strategic Breakthrough

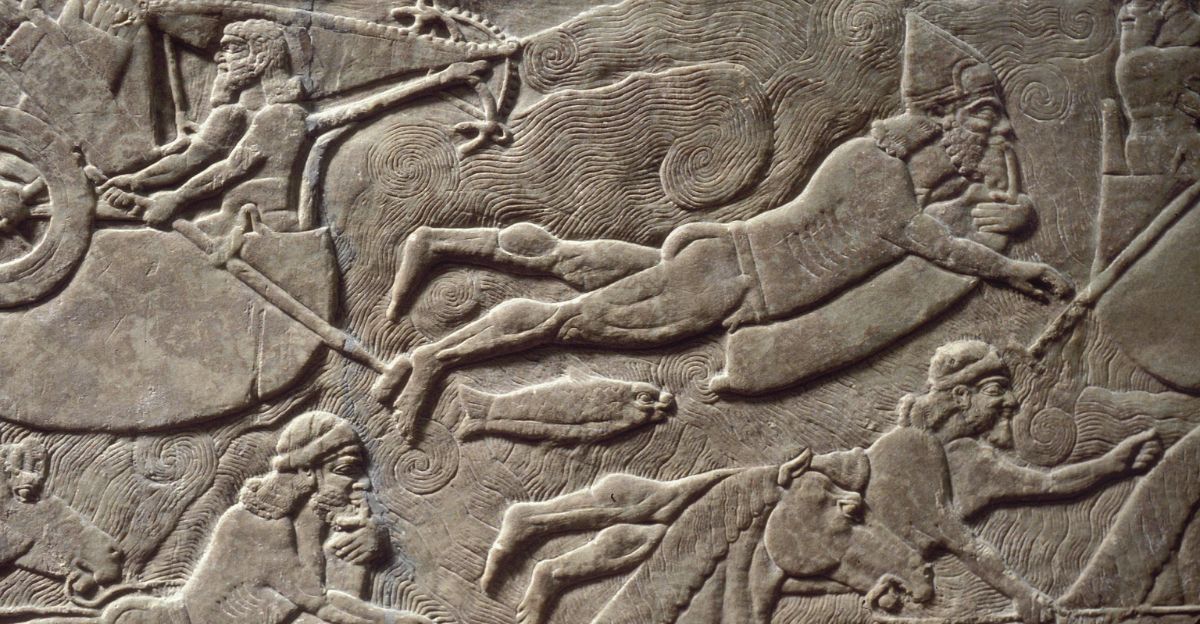

King Ashurnasirpal II ruled from 883-859 BC and revolutionized warfare tactics. His armies needed to cross multiple rivers, including the Euphrates and Tigris.

Traditional crossing methods alerted enemies and ruined the element of surprise crucial for Assyrian success. This led to an innovation that caught many armies off guard.

An Innovation Ahead Of Its Time

The breakthrough came with inflated animal skin flotation devices, which were shown in British Museum reliefs. Archaeological evidence confirms soldiers using goatskin bags as flotation aids while swimming.

Some modern interpretations speculate these could have served as a primitive breathing apparatus, though this remains unproven archaeologically.

Regional Devastation

These underwater techniques proved devastating across the ancient Middle East.

Assyrian forces appeared unexpectedly behind enemy walls in cities like Babylon and Damascus. The stealth crossings helped expand their empire dramatically within decades.

Terror Stories

Accounts of Assyrian soldiers’ efficiency in fighting highlight the terror stirred up at the time. King Ashurnasirpal II wrote about the fear these tactics created in his royal inscriptions.

His annals describe how enemies fled in panic when Assyrian soldiers emerged from rivers they thought provided protection from attack.

Enemy Response

Other civilizations took note of the innovations of the Assyrian underwater warfare and tried to copy them. Greeks later developed diving techniques using hollow reeds as breathing tubes.

The story of Greek diver Scyllis shows how these water tactics spread throughout the ancient world.

Technology Evolution

The goatskin devices represented crucial progress in the development of flotation equipment. These innovations came nearly 3,000 years before modern scuba gear was invented.

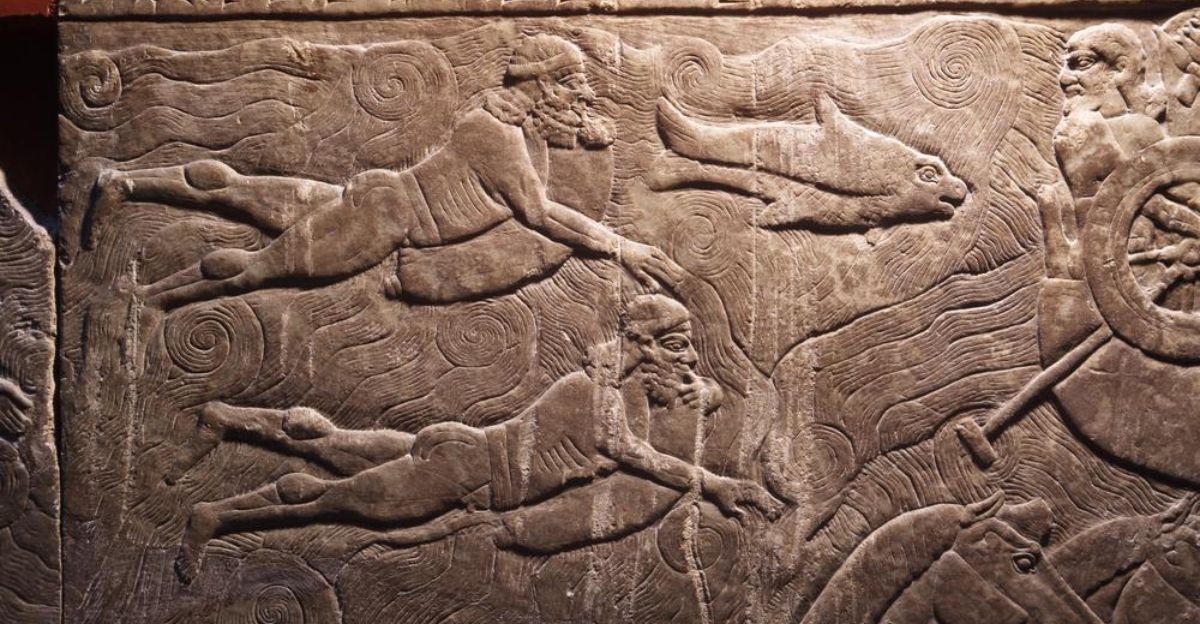

While the relief art shows figures appearing to breathe through tubes, experts debate whether this depicts actual underwater breathing or artistic convention.

Hidden Costs

Assyrian scribes record large-scale deportations after victories, moving skilled workers—farmers, metalworkers, and boatmen—into Assyrian territory.

Although the texts do not name “underwater” specialists, mass resettlement helped the empire control newly conquered regions.

Internal Challenges

Military commanders struggled with training specialized underwater units in palace records. The resource-intensive training required months of preparation and significant equipment investment.

Disputes arose over scarce goatskin allocation for military versus civilian use.

Leadership Decline

When King Ashurnasirpal II died in 859 BC, his successor failed to maintain innovation. Shalmaneser III campaigned for 31 years with decreasing success.

The empire’s underwater capabilities declined under conservative leadership, favoring traditional methods.

Revival Attempts

King Tiglath-Pileser III later tried restoring military innovation from 745-727 BC. He created advanced military reforms, including professional standing armies.

His changes included specialized units for developing warfare equipment and river-crossing techniques.

Expert Debate

Modern military historians question whether these ancient techniques were effective or mainly propaganda.

Archaeological evidence clearly shows flotation devices, but scholarly interpretations of the relief art depicting underwater breathing capabilities remain highly contested among experts.

Modern Questions

The Assyrian underwater warfare legacy raises important questions about military innovation and authoritarian regimes.

These ancient precedents remain relevant for understanding modern underwater military development and its broader political implications throughout history.

Political Impact

The Assyrian model combining advanced military technology with population control influenced later empires.

Persian, Greek, and Roman systems adopted similar approaches of technological superiority plus systematic population management.

Global Influence

These underwater techniques spread throughout the Mediterranean world through archaeological evidence. They influenced military doctrine from Egyptian naval operations to Roman river-crossing tactics.

The technological transfer crossed political boundaries despite ideological opposition.

Environmental Damage

Mass procurement of animal skins for flotation devices contributed to environmental problems. Systematic hunting depleted wildlife populations across the empire.

This resource extraction weakened the empire’s agricultural foundation over time.

Cultural Memory

Through art and literature, the underwater warrior image became embedded in ancient Middle Eastern culture. Later civilizations depicted aquatic soldiers as symbols of military power.

These depictions influenced classical mythology about warfare.

Today’s Relevance

Modern naval special forces employ similar principles of stealth water operations using flotation aids that the Assyrians pioneered thousands of years ago.

The ancient relief art shows underwater swimming with breathing tubes, though this interpretation remains speculative rather than archaeologically confirmed.